NOAA's New Atlas 15 is a Crucial Update for Climate Change Resilience

NOAA released an update to a key tool that informs climate resilience decisions for infrastructure

As we all watch the recovery from Hurricane Helene, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) released an update to a key tool that informs engineers, floodplain managers, developers, and municipal leaders across the country when they’re designing infrastructure to stand up to the anticipated frequency of large storms.

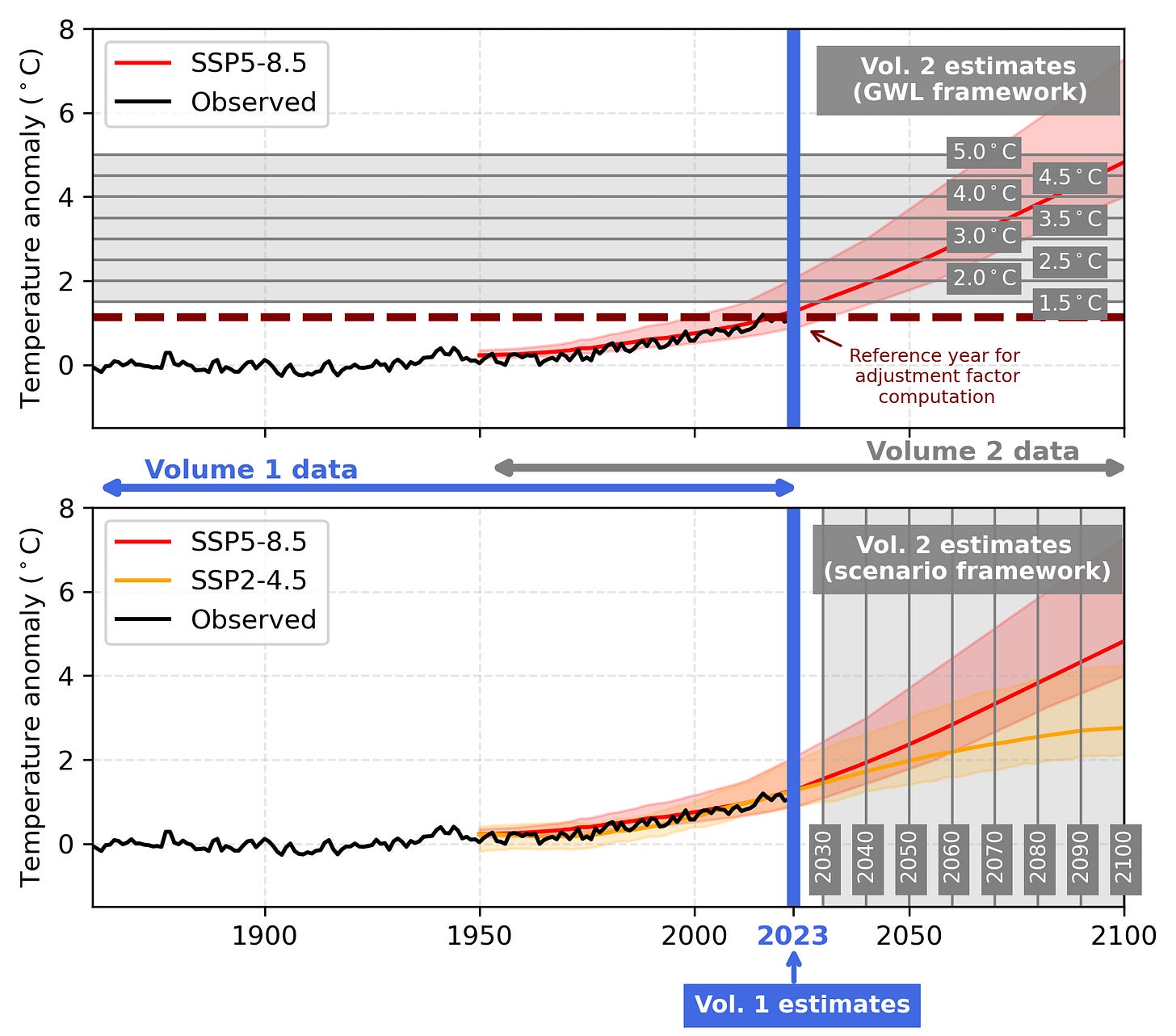

The new tool is called NOAA Atlas 15. Atlas 15 incorporates expected changes in future climate and precipitation patterns driven by global warming. Previous tools, like Atlas 14, were based only on historical climate data and didn’t account for how fast precipitation patterns were changing. As the pace of climate change quickened, that created myriad problems for designing major infrastructure projects. By the time projects based on the historical data were complete, the climate had already changed so significantly that the systems just built were already ill-equipped to handle altered weather patterns. It meant stormwater systems, sewers, water treatment plants and the like were sometimes obsolete the moment they were finished. It created a constant, expensive, demoralizing game of climate-infrastructure catch up.

In any part of the country, you can pull up the information from the older Atlas 14 that tells you what storm sizes to expect over a given period. A savvy user could compare that info to the size of storms actually recorded in a typical storm season. You would almost always find that the 10-, 25-, 50-, or 100-year storms of past decades are now occurring much more frequently. In southeast Michigan, for example, it’s now typical for us to see 3 or 4 “25-year storms (or larger) in a single year. That’s a clear sign the historical data isn’t representative of the current reality.

NOAA Atlas 15 is something those of us in the climate resilience field have wanted to see for a very long time, but reliably projecting the frequency of relatively infrequent, potentially damaging precipitation events is notoriously challenging. Such storms often occur over a short period of a few hours and were often missed or characterized incompletely by weather observations. Good statistics were lacking. The bit of sobering irony here is that as climate change made those damaging storms more frequent, it helped scientists gather enough data to incorporate into ever- improving models and make reliable projections.

Also encouraging is that NOAA certainly heard the needs of scientists and practitioners in the field over the past decade. They spent a lot of time gathering information from people that will actually use the data ensuring the new atlas will have a practical benefit to real-world projects.

There are several ways Atlas 15 will benefit us all, whether we realize it or not. Engineers, city planners, and developers can use this data to design and build structures that are more resilient to extreme precipitation events. This is crucial for ensuring the safety and longevity of infrastructure in the face of increasing climate variability. Communities will also be able to use Atlas 15 to better assess their flood risks and take appropriate measures to mitigate them. This includes updating floodplain maps, improving drainage systems, and implementing better land-use practices. Policy decisions at the local, state, and federal level can now more easily be made to match the reality we’re dealing with.

Perhaps most importantly, simply by incorporating future projections into these tools and by highlighting how fast precipitation patterns are changing, it may help decision makers realize just how drastically we’ve altered the climate, how fast risks are changing, and how dynamic the solutions need to be. If we design a major infrastructure system to last, say, 100 years, are we building it for the climate of today, the climate of 50 years from now, or 100 years from now? Some of those options will be cost-prohibitive; others will be physically infeasible. Yet, even asking this question drives home a central challenge in climate adaptation: We will not be able to out-build climate change. We can do our best to future-proof our systems and reduce risks with better-prepared infrastructure, but beyond that, we will need to get dynamic solutions in place. That means we’ll need less reliance on static, built systems and more widespread use of nature-based systems. We will need to protect more land, allow for more green space, protect floodplains and wetlands that attenuate flood risks, and in some cases, begin managed retreat from high-risk areas.

Hard challenges lie ahead, but NOAA’s Atlas 15 will be an essential tool for navigating them.