The Beef with Big Beef

The beef industry is now waging an all-out war of deception to protect its profits at the expense of the environment and public health. Here's what the science says.

The science is clear: Beef production harms the environment and is a significant contributor to climate change.

While attending a climate change conference in 2014, I was eating one of those typical boxed sandwich lunches they set out for people to grab as they filter into a main hall from each of the smaller session rooms. I got to the lunch line late, so the only option left was roast beef. Another conference goer had given me a short stack of research papers to flip through. One of them was a paper in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences (PNAS) by Gidon Eshel and collaborators. The research evaluated the natural resource burdens of livestock production. By the time I got through the abstract, I’d stopped chewing and set my sandwich down.

That study found that producing beef is far more resource-intensive than producing any other type of food. From calving to plate, beef is responsible for 5 to 10 times the greenhouse gas burden of other meats. With a few exceptions, it's 11 times the burden of even the most carbon intensive vegetables and nuts. In comparison to potatoes, wheat, and rice, it requires 160 times the land. Compared to chicken and pork, it requires 11 times more water. It is often produced in areas where the land and water are already sensitive to use.

Later studies using different, independent methods have found similar results. There is always some variability depending on what exactly is considered and where the consumers are assumed to be. In some cases, turkey looks a bit better than chicken. Or maybe some nuts looks worse than in other studies. Lamb sometimes competes for worst option with beef in certain European markets. Lobster and crab can blow up your carbon footprint if you’re eating them freshly flown across the country, but if you’re eating them right off the boat in Maine, they are one of the more sustainable protein options. Across the body of research however, beef almost always has the worst environmental burden.

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that the meat and dairy industry produces 14.5% of global planet-warming emissions. That’s more than half of the environmental impact of all food production, and beef production accounts for a significant portion of meat and dairy emissions.

Hannah Ritchie’s meta-analysis from 2020 has been widely shared. She and her colleagues found that producing 1 kg of beef results in 71 to 100 kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions. Beef is about 7 to 10 times worse for the climate than chicken, up to 100 times worse that peas or bananas, and more than 200 times as bad as apples, nuts, or root vegetables.

A University of Michigan analysis found animal products contribute to over 80% of total greenhouse gas emissions from food consumption while vegetables, fruits, and grains contribute less than 5%.

Beef production doesn’t just directly cause climate change by increasing greenhouse gas emissions. It also handicaps ecosystems’ ability to respond to climate change or sequester carbon from the environment. When more water and land is used to produce cattle or livestock, there are less resources for the long-term ecological functions that keep soil, water, flora, and fauna healthy.

An investigation of land use by Bloomberg News highlighted the broader impacts of beef production. Approximately 41% of US land is used for livestock production and livestock feed. The majority of that land is used to raise cattle, and that doesn’t include feed exports going to raise cattle elsewhere. The amount of land protected as wilderness pales in comparison. A quick glance at the map and one can see that the United States has become primarily—by land use at least—a corn, beef, and dairy production mechanism. It's remarkable just how far our national economy has contorted itself to serve an energy-intensive, multi-step, high-risk, expensive food source. It’s plainly unsustainable.

When the environmental damage and demands caused by cattle production intersect other effects of climate change, like reduced water availability in the American Southwest, all problems are amplified.

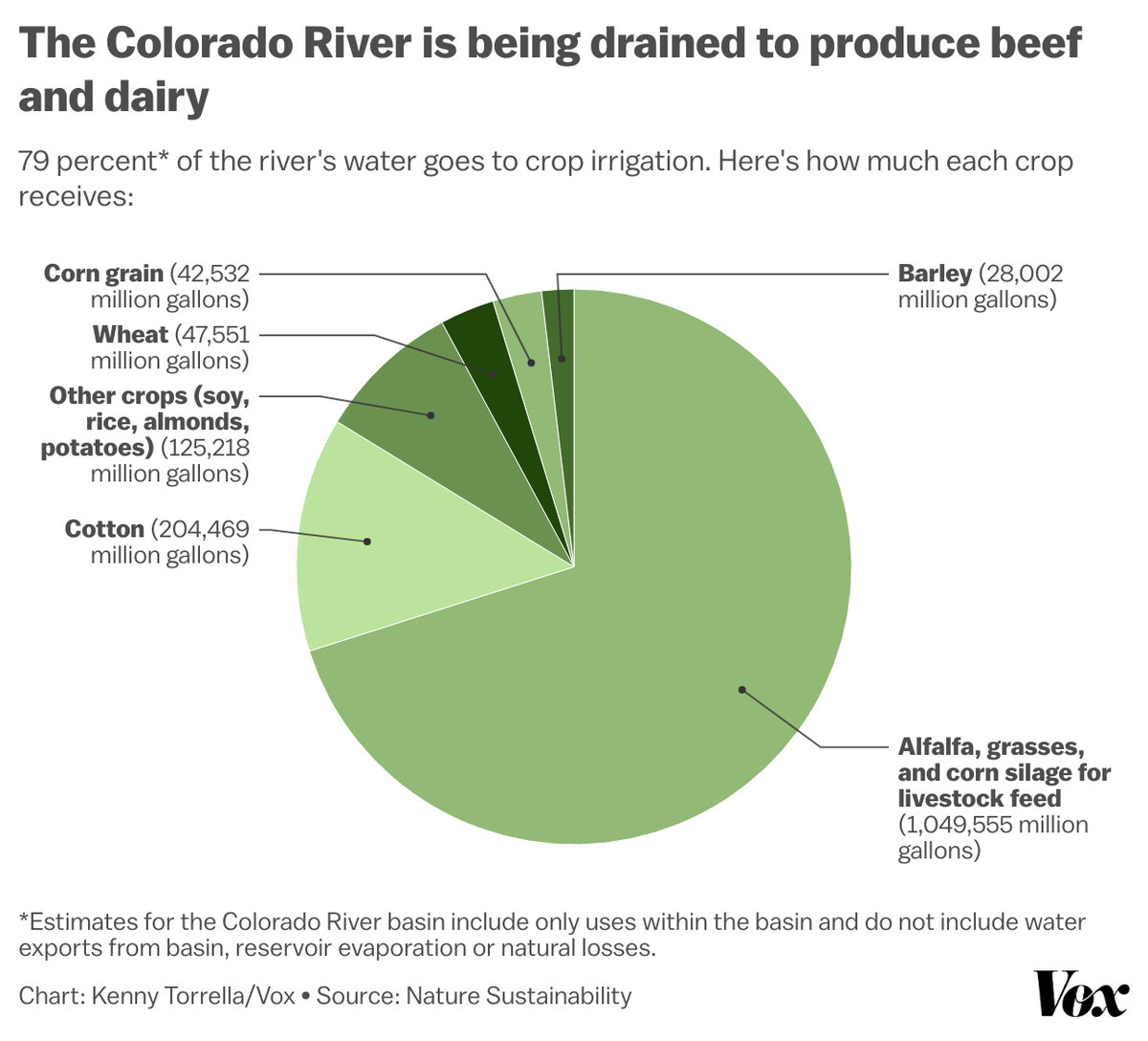

In April 2023, Kenny Torrella reported on the how cattle feed crops are the major source of water use from an already stressed Colorado River. Nearly 80% of water drawn from the Colorado is used for agriculture. Of that, cattle feed crops take about 70%, all to fatten beef and dairy cows. It’s using an unsustainable amount of water withdrawn for unsustainable food types in a part of North America that many experts believe is unsustainable for all but the least demanding crops. And that use of natural resources imperils the other needs for that water, be they ecological requirements or more pressing human needs.

Big Beef Follows the Big Oil and Big Tobacco Deception Playbook

Using tactics from Big Tobacco, Big Oil, the lead industry, and others, the beef industry has mobilized a disinformation army to combat the scientific reality that beef production harms the planet and is a significant contributor to climate change. They’ve even turned to a old scam artists’ trick, inventing a fake, official-sounding “degree” program.

I’m not going to repeat the claims from this widespread misinformation campaign, but they are circulating on Facebook, Twitter, and other social media, often amplified by bot accounts targeting communities with a heavy economic reliance on beef production to spread lies rapidly.

A recent “leaked” draft of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report released on March 20, 2023 showed the extent of the beef industry’s political reach. Leaning on supportive political delegations from Brazil and Argentina, major beef producers, they forced the IPCC to revise the language of Summary Report for Policymakers. The report’s scientific authors recommended a shift to plant-based diets, explaining that “plant-based diets can reduce GHG emissions by up to 50% compared to the average emission-intensive Western diet.” That is what the science indicates and what the full report details in many more words.

But the published summary report that political leaders and journalists read changed the line to “balanced, sustainable healthy diets acknowledging nutritional needs.” That avoids calling out beef and dairy, recommendations for what a sustainable diet includes, and doesn’t make reference to the problematic food production model in Western, affluent countries.

These sorts of political edits sometimes interfere with the IPCC’s messaging, and it’s a major reason why many scientists call describe the IPCC summary reports as rigorously-vetted but conservative assessments of the status of climate science. The full reports tend to better indicate the state of the science and the scale of the crisis.

In this case, however, the edit demonstrates that the beef industry has a real problem with the facts, significant influence at the international level, and want to hide the negative effects of their products.

Why is Beef so Bad for the Environment?

Beef production is bad for the environment and a major contributor to climate change because it requires significantly more land, energy, water, nutrients, and time to raise cattle and get beef to your plate.

Cows must be raised, requiring feed that must be grown. Feed crops aren’t suitable for human consumption and have been cultivated to feed animals, so all the land, water, nutrients, and energy required to make feed are emissions attributable to livestock. If there were no cows, there’d be no feed required to fatten up the cows.

The feed is shipped across the country or around the world, often by rail, often requiring large trucks to link the supply chain together, and then is taken to farms by other typically large trucks. Carbon dioxide is emitted from tailpipes and smokestacks along the way.

The cows eat the feed and require lots of land and water. Ranchers have optimized how fast they can grow cattle to a profitable weight before slaughter, but it still takes years. Cattle ranching is hard work, requiring lots of energy for staff, facilities, and supporting services to keep the cattle safe and healthy. And note that many analyses do not include the energy required to regulate and evaluate farms for public health requirements and food safety.

The cows then need to be slaughtered, processed, and in most cases, the meat needs to be frozen. All that requires even more energy and emissions from transporting cattle back and forth. The unused remains of the cows also need to be disposed of properly, so more energy is needed.

The beef arrives at the grocery store, where it must remain frozen or refrigerated, and attended to by butchers, requiring yet more energy. People drive to the grocery store, pick up their pound of hamburger meat, drive back home, put the beef in the freezer, requiring yet more energy every step of the way. Then they have to cook it, sometimes on gas stoves, emitting another final dab of fossil fuel use before serving it to their families.

There are many steps from raising feed, birthing a calf, raising the cow, and getting a meal to your plate, and each step is more energy intensive than for other food types.

The Curious Want of Beef Loopholes

Even among folks open to changing their diets, I find that people often hear all that information, think it through, and try and find loopholes in the system. I won’t guess what the psychological reasons are behind this skepticism, but I’ve witnessed it on numerous occasions, and it’s something the beef industry is rapidly learning to exploit with misinformation.

People will ask something some version of this question: “What if we only eat grass-fed, locally, raised, organic, non-GMO, well-loved cattle from down the road and we are personal friends with the rancher that personally slaughters and processes the cows?” In that optimal case, would the carbon footprint be acceptable, they wonder.

The science suggests that emissions might be lower than for some other food types, but still much higher than most and way higher than if you went to similar lengths to sustainably source other foods. Even in the absolute, best case scenario, adding up all the best practices around sustainable beef, the emissions saved might amount to a 30% compared to typical USDA beef in a grocery store.

Not to mention, the scenario described isn’t remotely scalable to feeding any significant number of people, not by a long shot, and in some analyses, grass-fed cattle can actually lead to greater emissions, depending on where it comes from. Cattle feedlots that draw ire from animal rights activists can actually be energy efficient compared to other means of raising cattle. They are, after all, food manufacturing facilities built to maximize profit by turning out as much beef as possible in the shortest amount of time with the fewest resources committed. It’s a dim outlook for cows on feedlots, but the cattle are managed as commodities with industrial proficiency.

Eat Less Beef: The Simplest Climate Action

The data is abundantly clear. Global beef consumption, and the American model of beef production, is undeniably unsustainable. We need to eat far less beef, and the way we raise cattle needs to change dramatically.

This makes no statement on the treatment of animals, nor is it a cry for vegetarianism or veganism on moral principle. It's simply a mathematical reality that we can't eat this much beef. It's a tremendous burden on our ecosystems, and it's a huge part of our carbon emissions.

The good news is that the solution to the problems of beef consumption is, at the heart of it all, quite simple: Don’t eat beef.

That’s it. There’s no tax, no hidden fee, no commitment, just don’t buy beef, and choose other foods when you can. Eating less beef is the most cost-effective action an individual or family can take to reduce their own carbon emissions and push the food industry to be more sustainable.

The benefits of eating less beef is significant but hard to comprehend, so it’s worth putting the numbers in context.

According the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, transitioning to a plant-based diet would significantly reduce planet-warming emissions and relieve enormous stresses on the environment. Changes to our diets would reduce global carbon dioxide emissions by 8 billion tons per year and free up millions of square kilometers of land.

A 2006 study calculated that by following a plant-based diet, the average American can reduce their carbon footprint to the same degree as swapping out an SUV for the average sedan. Since beef is such a significant part of the average American’s carbon emissions, eating less beef can have as great an impact as driving a more fuel-efficient vehicle.

The University of Michigan found that eating just one vegetarian meal per week could avoid the equivalent emissions of driving 1,160 miles.

According to an analysis by the NRDC, between 2005 and 2014, Americans modestly changed their diets and their related, per capita, planet-warming emission dropped by about 10 percent, equating to roughly 271 million metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions avoided. That’s roughly the equivalent of the annual carbon emissions from 57 million cars. Most of the drop in emissions from that period was because Americans bought about 20 percent less beef, consistent with the average American home eating beef one less time every week or two. (Beef consumption has risen again since then.) That small change in eating habits, something most people barely noticed, avoided 185 million metric tons of planet-warming emissions—roughly the equivalent of the annual tailpipe pollution of 39 million cars. That's 8 times the number of vehicles you’d see on a populous state like Massachusetts on an average day.

Sustainable Alternatives Arise

There is some room for optimism. The impacts of beef have caused innovators to find alternatives. Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat are two examples of companies trying to find plant-based alternatives to beef that are, to most people, indistinguishable from ground beef. Give one of these burgers a try. You’ll be impressed. (I have to admit the Impossible Whopper, sold by Burger King, tastes better to me than a traditional Whopper.) Other alternatives include actually growing animal meat in a lab or getting people to prefer things that not the same as beef.

In a Substack post, Hannah Ritchie looked at data evaluating the carbon footprints of these alternatives compared to traditional beef. Eating a Beyond Burger or an Impossible Burger cuts your burger-related emissions by about 96% compared to chowing down on a beef burger. These results are encouraging, especially since the costs and production inefficiencies of alternatives will come down as production scales up to meat growing demand.

A Beefless Future Leaves More Room to Live and Grow

Eventually, the costs of producing beef alternatives become lower than the cost of actually raising cows. I can imagine a future, decades from now, after the ranching and corn lobbies have extended their industry subsidies well past their natural lifetimes, when plant-based beef alternatives are the norm. The future our children or grandchildren retire into may be one in which unnecessarily consuming cattle is rare, perhaps even considered taboo.

It reminds me of a scene from the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode Lonely Among Us, in which Commander Riker declares, “We no longer enslave animals for food purposes.” When pressed by another character why they’ve seen humans eating meat, he replies again, “You've seen something as fresh and tasty as meat, but inorganically materialized, out of patterns used by our transporters.” Indeed, future generations might look back on the raising of animals just for slaughter with some disgust, seeing it as a grotesque artifact of societal evolution in a more primitive state.

Long before we reach that point, we’ll see positive cascading effects of declining beef consumption that advance many climate solutions. With less demand for land once used for cattle production, land conservancies and growers of other crops with lower carbon footprints may be able to move in. By growing food-to-table crops, like fruits and vegetables, and by restoring ranchland into natural areas, we could take significant steps toward the recommendations of the IPCC to improve working lands and protect half of all global ecosystems. That will further reduce carbon emissions while making communities more resilient for people and wildlife.